In baseball, a player’s batting average is the number of base hits per times at bat. The higher your batting average, the more valuable you are. In learning and development, your “batting average” is how often you improve performance per training initiative. The higher your batting average, the more valuable you are.

In baseball, a player’s batting average is the number of base hits per times at bat. The higher your batting average, the more valuable you are. In learning and development, your “batting average” is how often you improve performance per training initiative. The higher your batting average, the more valuable you are.

Unfortunately, evidence suggests that training’s batting average is not as good as it could be. When we ask participants in the Learning Transfer Certificate Program “What percent of trainees use what they learn long enough and well enough after training that they actually improve their performance?” they routinely estimate only 10 to 20 percent. When McKinsey asked executives about the effectiveness of training, only 25 percent said their training programs measurably improved business performance.

In this new series of blog posts, we will examine how trainers and training departments can improve their “batting averages” to deliver greater value to their organizations and, by doing so, increase their own value and prestige.

Training Is Not a Cure-All

High-performing batters know when to “hold their swing”; they don’t try to hit every pitch that comes their way. Similarly, one of the fastest ways to improve the overall effectiveness of training is to stop fulfilling every request for training pitched our way.

Employees’ performance is determined by factors at three levels: the worker (knowledge, skills, attitudes), the work (job structure, process design), and the workplace (corporate organization, policies, and culture). Issues at any of the three levels can adversely affect performance.

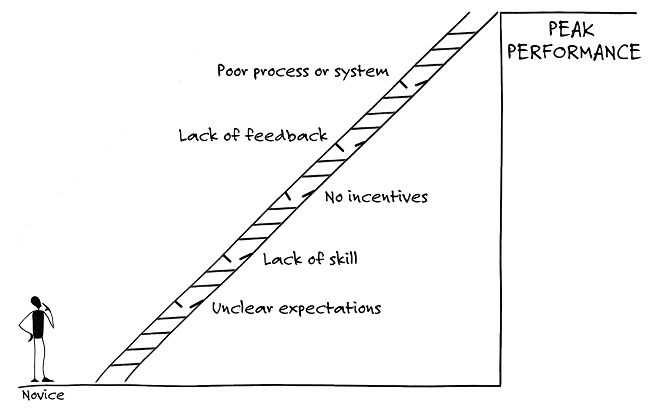

There are many potential causes of suboptimal performance besides a lack of skill or knowledge.

Copyright 2014, The 6Ds Company. Used with permission.

Training resolves only one cause of poor performance: insufficient skill or knowledge at the worker level. If the root cause of the performance gap is something else—such as unclear expectations, a lack of meaningful feedback on performance, or a poorly-designed work process—then training will not solve the problem and could even make it worse.

Many business managers mistakenly think of training as a sort of cure-all. Faced with any performance shortfall, they request a training program, without really thinking through the fundamental issues. When training departments, in their eagerness to be of service, fulfill such requests without first making sure that training is appropriate, they lower their batting average. The training—no matter how well designed and delivered—fails because it was not the right solution to begin with.

How often does this happen? To our surprise and dismay, participants in our Learning Transfer Certificate Program estimate that as much as 50 percent of the training they do is “dead on arrival” because it does not address the real cause of the performance issues.

How do we prevent the misuse of training and increase our batting average? We need to educate business managers about when training is—and is not—an appropriate intervention. We need to differentiate issues of “skill” versus issues of “will” by asking: “Could they do it if their lives depended on it?” If employees can perform if they really have to, then as Bob Mager taught us: “You can forget training as a potential solution.”

We need to redefine ourselves as being in the performance enhancement business, rather than the training business. That means helping our clients find the most effective solution—whether or not that includes training. Lastly, we need to remember that “even when training is part of the solution, it is never the whole solution”—a topic we will address in future blog posts in this series.